Mapping the Immigrant Experience with Yu-Wen Wu

For Yu-Wen Wu, mapping is an emotion; it is labor, excavation, a walk with memory, conviction and longing. Since I met the artist at a friend’s house in November, I’ve been thinking about how best to illustrate her great significance in this city — her journey, artistic approach, unique material vocabulary and impressive resistance to categorization. After a lot of thought, I realized that what generates the most meaning for me — the red thread that connects the work — is this relationship to mapping. This idea that mapping is about so much more than geography or distance or growth or even spans of time.

Yu-Wen Wu moved to the United States from Taiwan when she was six years old, and her art explores, on its deepest level, the immigrant experience. How is a young girl’s sense of self impacted by moving to a new country and leaving the old one behind? What are the long term effects of assimilation, displacement, feelings of invisibility? How can one hold on to one’s birth culture while navigating a new culture that is at first foreign and then quickly dominant, as in hegemonic, as in, this is the way you must act, speak, move, look and think, or else? Questions like this rang out from the audience following a talk at Harvard to celebrate Wu’s piece “Walking to Taipei” included in the “Journeys” exhibit on view through June 2, 2024 at the Harvard Art Museums. Again and again, people took the opportunity to describe the way Wu’s art spoke to their own complicated feelings about being an immigrant or from an immigrant family.

WALKING TO TAIPEI

“Walking to Taipei'' came together over the course of ten years. Wu started it when she was missing her grandmother, the woman who raised her and who features prominently in her body of work. Unable to buy a flight to Taiwan, Wu asked Google for walking directions from Boston to Taipei City. And in what she considers a gift from the Internet, Google delivered 2,052 lines of directions for walking the 11,749 miles over the course of 155 days and 5 hours, which, when she printed them out, came to 94 pages of surreal instructions.

Over the following decade, in between work on other projects, Wu experimented with various ways to unpack and remake that gift. Formally, she wanted to honor tradition, but not repeat it. The result, a contemporary take on the ancient East Asian handscroll, is rife with longing, humor, precision, imagination and wit. There are a number of strong works in the Harvard show (Watanbe Gentai’s “Peach Blossom Spring” uses the color blue to exceptional ends) but “Walking to Taipei” is the reason to visit. It’s the kind of weighty contemporary centerpiece the MFA’s Hallyu! show so glaringly lacks.

“Walking to Taipei,” Harvard Art Museums/ Fogg Museum. Photo: Robin Hauck

Wu printed the directions on paper the color of papyrus and painstakingly cut out each step. She adhered them (they read from right to left) to a 300 inch scroll she made with Dura-Lar and a handmade frontispiece and endpiece attached to acrylic rollers. With a nod to geometric abstraction (think Kazimir Malevich or Varvara Stepanova’s Soviet textiles) she arranged the individual steps in varying patterns, creating segments of cascades, ripples and curves. At 20 feet long, the work unfolds over time. The Harvard curators roll and unroll the ends to reveal new parts of the scroll every month. The experience is absorbingly paradoxical - each step is simultaneously ludicrous (jet ski, ferry and swim to Taiwan?) and graphically intriguing.

When I asked how maps make her feel, Wu explained, “Maps allow me to step back — viewing the overall terrain from 10,000 feet for instance. Maps allow us to see connections in different systems. It’s an interesting perspective, but it doesn't convey what it's like when you’re walking on the road, seeing the color and texture of the path, experiencing the rocks and pebbles and the uneven ground beneath your feet. What kind of vegetation is around you, what sounds surround you, are you in the city or in the country? With ‘Walking to Taipei’, I wanted to create a map that leaves room to envision and experience a journey in your own way.”

Considering Wu’s enormous artistic output, her humility is striking. It’s part of what makes her work so powerful. Though “Walking to Taipei” charts an emotionally (and technologically - the results are impossible to replicate) individual experience, it reflects the impulse in all of us to connect with those who make us who we are, who come from where we come from.

“Walking to Taipei” is also a complex data visualization. Designing elegant structures that portray complex data sets is one of Wu’s artistic superpowers. One of my favorite examples is “Global Migration,” in which she created a graphical representation of the 68.5 million people displaced in 2018 in gold ink and graphite on Dura-Lar.

“Global Migration Map,” 2018 gold ink, graphite. Image courtesy of the artist.

TERRAIN

According to Google it takes 15 minutes to walk the 0.6 miles from the Harvard Art Museums’ “Journey” exhibit to the Chao Center at Harvard Business School. Here you can see another example of Wu’s mapping prowess, her permanent installation “Terrain.” “Terrain” is a 38-foot-long sculptural metal drawing in which abstracted topographical lines inspired by the Song dynasty and Hudson River School landscape painting traditions intertwine with a mountainous line made by mapping 100 years of the S&P 500. How better to represent the role of business in a world struggling to resolve the needs and influences of people walking infinitely different paths?

The Harvard acquisition of “Walking to Taipei” reflects a recognition by the art world of Wu’s influence. One of three winners of 2023’s prestigious James and Audrey Foster prize presented by the ICA Boston, Wu staged an exhibition showcasing her contemplative, process-centered practice across sculpture, drawing, video and site-specific installation. The show brought visitors on a journey through the recurrent themes and materiality of her practice and established her at last among the region’s most important contemporary artists. The Foster Prize came on the heels of an influential recognition by renowned New York Magazine senior art critic Jerry Saltz for her show at the Independent Art Fair in 2022 and the expansion of her celebrated public art project “Lantern Stories” to San Francisco in October of 2022. She has also been invited to the prestigious Artist-in-Residence program at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum this year and will create new artwork to be installed on the Anne H. Fitzpatrick Façade in 2025.

It’s about time. Her subjects – memory, immigration, cultural identity, assimilation, change, The American Dream, navigation and our relationships with nature and data – could not be more urgent. As we inch queasily toward a presidential election in which we can count on real human issues being bastardized beyond recognition, Yu-Wen Wu’s art keeps the focus on what matters, in works that make us think long after we’ve stepped away from the art.

THE FOSTER PRIZE AT THE ICA BOSTON

Wu thought a lot about mutability and transformation when creating her Foster Prize show, “States of Being.”

In “Intentions,” orbs formed from tea, dipped in gold and wrapped in red thread hang from the ceiling in eight red columns which pool in coils on their white plinth. Inspired by the artist’s memories of sitting on her grandmother’s lap when she would recite prayers, “Intentions” centered the ICA exhibition the way a mantra centers a rush of thoughts. (If you happen to find yourself at the Quin House in Boston don’t miss the single strand piece from the same series installed in the Living Room.) Wu collects post-brewed tea from her aunt in Taipei and her mother in New Jersey as a way to incorporate family and culture into her work. In “Intentions,” the tea has been cast into something solid, the rutted texture allows it to be held on to, unlike the source material which naturally disintegrates over time.

“Intentions III” 2023. Gilded tea leaves and red string. Image courtesy of the artist.

Red thread factors prominently. Wu’s grandmother tied red thread bracelets around her and her siblings' wrists when they were born. In Asian and Asian American cultures, the color red represents happiness and good fortune. Here Wu says, it also represents family bloodlines. In one wall of the ICA show, a series of small works - porcelain cast leaves, repaired stones, small drawings - are linked on the wall by a traveling red thread.

“Acculturation” 2023 is a mounted arrangement of found, gilded leaves and stems spanning one entire wall of the exhibit. While her studio is in the urban Fort Point neighborhood of Boston, Wu ventures into nature often, always with a pair of shears for the leaf or branch that catches her eye.

“Acculturation” grew out of an earlier series entitled “Not All Alike” created with only tea leaves which was a response to “invisibility and the conflation of identity.” “Acculturation” is composed of the leaves, branches and stems of various plants and trees, cut and recombined into meticulous new forms. Americans are all mutts after all, made up of many different parts, with wide-ranging origins. She’s careful to choose leaves that are not easily identifiable, the point is the endless combinability, the melding of the original parts into the new whole. Some of the assemblages are dipped in gold completely, some partially, some not at all. Not all who come to America, she explains, get to live the American Dream.

“Acculturation,” 2023. Found and gilded leaves.

Gold plays a very important role in Yu-Wen Wu’s practice as do other culturally significant materials like the tea and red string, lanterns and maps. In the mid 1800s thousands of Chinese immigrants flocked to California hoping to strike it rich in the gold rush. For Asian immigrants, California became known as gam saan, or "gold mountain.” She recalls herself as a child imagining American cities with streets paved in gold. Symbolically it speaks to both opportunity and false promises. Aesthetically, gold is a part of Wu’s signature vernacular, a consistent color starring in the intentionally restrained palate of her body of work.

WITH/OUT WATER

In a response many creatives may find familiar, Wu’s family initially rebuffed her dream of becoming an artist. Intending instead to pursue science, she attended Brown University as an undergrad and ultimately moved to Boston in 1981 to work as a research assistant for Nobel Prize-winning neurophysiologist David H. Hubel. This experience rerouted her life trajectory and ultimately made a lasting impact on her art.

Consequently, art and science conspire to provoke inquiry and making in the artist’s imagination. In 2018 Wu received a grant from the Union of Concerned Scientists to create her first outdoor public artwork addressing climate change and raising awareness of related global and local displacement of marginalized communities. She worked with the Asian Community Development Corporation (ACDC) and the Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center (BCNC’s) Pao Arts Center to create a community supported installation in One Greenway Park on Hudson Street.

WITH/OUT WATER, 2018 was composed of five nylon tents erected side by side and a six hour HD video montage projected onto the outside surfaces of the tents from within. WITH/OUT WATER spoke to the extreme weather, from drought to flooding, being experienced due to climate change and the impact on vulnerable populations. In Boston it addressed the lack of resources to aid certain communities during extreme weather — storm surges in particular. It also addressed the housing crisis, calling to mind temporary shelters erected for unhoused people in Boston and all over the world. WITH/OUT WATER was sited on land where in the 1960’s Massachusetts forcibly displaced hundreds of predominantly Chinese and Syrian immigrant families to make room for a new highway.

Wu held weekly listening sessions with ACDC’s 66 Hudson residents and youth program participants through A-VOYCE. Community members and visitors were very involved. Wu invited them to post their questions and comments on flags near the tents. The question infiltrated the park and the community - how will Chinatown be affected if the sea level continues to rise?

“My public artwork always has a community component,” Wu explained. “I spend a lot of time observing and being present within the site. I watch how the site is used, observe the relationship between the city, the park, the people and how it’s utilized. I hold community listening sessions to be mindful of a community’s needs. What can my public artwork contribute to someone who walks this route every day, for someone who spends time in the park daily and for the children who play there? What are the elements in these people’s lives that I can enhance?”

LANTERN STORIES

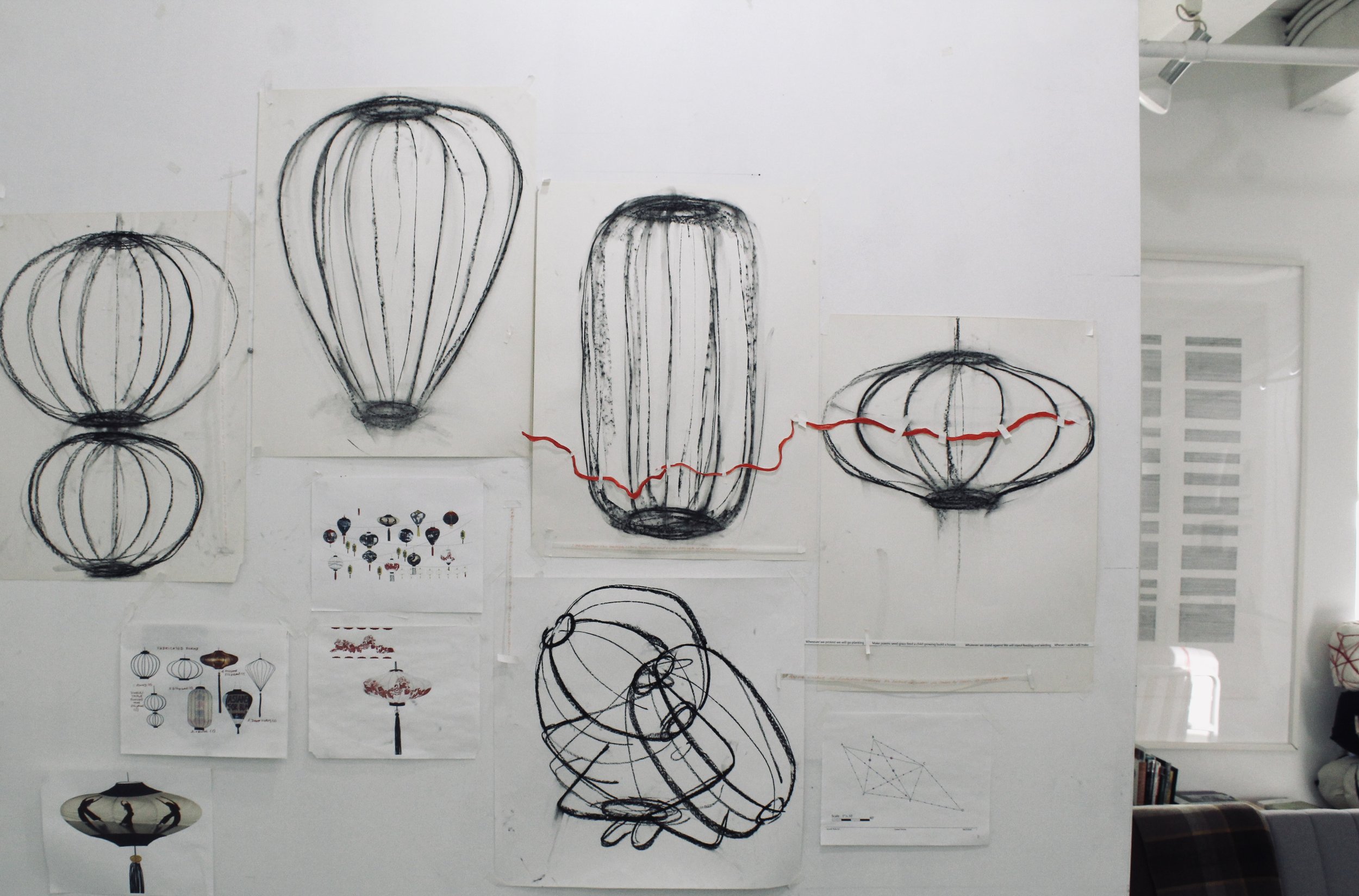

Collectively envisioning a way forward requires light. Illumination plays a role in many of Wu’s installation and video work, none more so than in “Lantern Stories.” First commissioned by the Greenway Conservancy in 2020, “Lantern Stories” is a public art installation of 31 lanterns depicting scenes of the history of Chinese immigration and the current realities of Asian American immigrants. In spite of the pandemic, “Lantern Stories” was joyously exhibited in the fall of 2020 at Auntie Kay and Uncle Frank Chin Park in Boston’s Chinatown. It was recommissioned in a new iteration for 2022. That year Wu expanded the work to San Francisco’s Chinatown, establishing a bicoastal dialogue between communities and citizens and expanding its impact nationally. Crafted in a variety of shapes and colors reflecting the iconic history of the object, Wu’s lanterns incorporated archival photographs, drawings, paintings and collage to tell the stories she sourced.

“Lantern Stories,” installed in Chinatown San Francisco, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist

As she has in many of her public projects, Wu organized listening sessions with community members. Residents of Chinatown shared memories, concerns and dreams. In its 2021 iteration, “Lantern Stories” evolved over the course of the pandemic, BLM and the rise of hate crimes against Asian Americans.

“Lantern Stories,” installed in Boston Chinatown’s Auntie Kay and Uncle Frank Chin Park, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist

Wu told me: “‘Lantern Stories' was focused on telling the story of immigration. Boston Chinatown has a fascinating history and so many stories that need to be told. Most of them were collected. When I received this commission I was imagining an abstract, very gestural light-based project that would shift and move. However after being involved in the community listening sessions that I implemented, it became evident that what the community desired was to relate stories and reflect upon historical memory. Honoring tradition without replication is the heart of this project… [I use] materials often with associations and metaphors particular to the Asian culture. To honor traditions with a contemporary point of view.”

“I always try to include a new conversation that we need to look into more deeply.”

One of her goals is to generate civic dialogue and promote education. In time, she hopes to expand “Lantern Stories” into a national project.

Like the towering silver moon drawing that illuminated her Foster Prize show, the 31 lanterns of “Lantern Stories” illuminated Chinatown’s streets as they illuminated its history and cultural traditions. While sharing many of the hardships experienced by Asians coming to America, the lanterns also emphasize the strength and resiliency of the AAPI community and the light that guides the way toward a more peaceful and inclusive future.

LEAVINGS / BELONGINGS

Work cannot be made in a vacuum and maps cannot be drawn without collecting as much information as possible about the area of interest. To further recognize and honor the experiences of those displaced from their home countries, Wu created “Leavings/Belongings,” a durational multi-part project that centers listening, storytelling, collaboration and female labor.

“Leavings/Belongings” at the Pao Arts Center. The line of bundles was accompanied by portraits of the participants and Wu’s signature red connecting thread. Image courtesy of the artist.

Wu has said, “Human migration will be a defining issue of this century.” Her artistic response makes physical the personal stories of hundreds of migrant people and refugees who have fled violence, armed conflict, hunger and economic hardship at home in search of a better life.

A bundle covered in writing. Image courtesy of the artist.

“Leavings/Belongings,” was originally conceived with artist Harriet Bart of Minneapolis. Due to distance and time, they developed the project in different ways.

Wu hosts community listening workshops and invites participants to create symbolic cloth-wrapped bundles while sharing their stories. A significant amount of this work she completed in 2019 while an artist in resident at the Pao Arts Center in Boston’s Chinatown. Women choose their bundle fabric and how they want to wrap them from material Wu has collected from all over the world. They fold their stories, fears and dreams inside, notes sewn to the outside. In the safe space, they create unique sculptures representing not only the physical objects but the cultural and emotional weight they carry with them or have left behind.

In addition to the Pao Arts Center, organizations with whom Wu has partnered for this project include the Refugee and Immigrant Well-being Organization in Albuquerque, NM; Economic Opportunities in Portland, ME; the Southeast Asian Coalition in Worcester, MA; Smith College and the Adelante Women’s Collective along with artist Harriet Bart in Santa Fe, NM as part of the exhibition “Displaced: Contemporary Artists Confront the Global Refugee Crisis.”

“Leavings/Belongings” bundles installed in a shipping container for HubWeek, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Hundreds of these bundles then become the material of Wu’s large-scale sculptural installations, such as exhibitions at the Pao Arts Center and at SITE Santa Fe. In 2019, the artist piled 500 community made bundles and stories in an open 6x6x6 foot cargo container for HubWeek’s forum titled “Foreign Born, Boston Based, Immigrant Led.” Prior installations include a 30 foot video on the subject of mass global migration and photographic portraits of the participants. Her installation at the Pao Arts center was haunting, hundreds of bundles displayed in a linear form, which like the images of desperate Mexican migrants in photographs by Ada Trillo, “recall the long lines of exodus as refugees flee.”

By giving refugees and immigrants a chance to tell their stories their way, Wu provides viewers the chance to see them more intimately, thus confronting the curse of invisibility too often cast on women and immigrants in this country. As in all her community projects, Wu stands in solidarity with her collaborators, refusing the objectification or voyeurism often accompanying government and news media accounts.

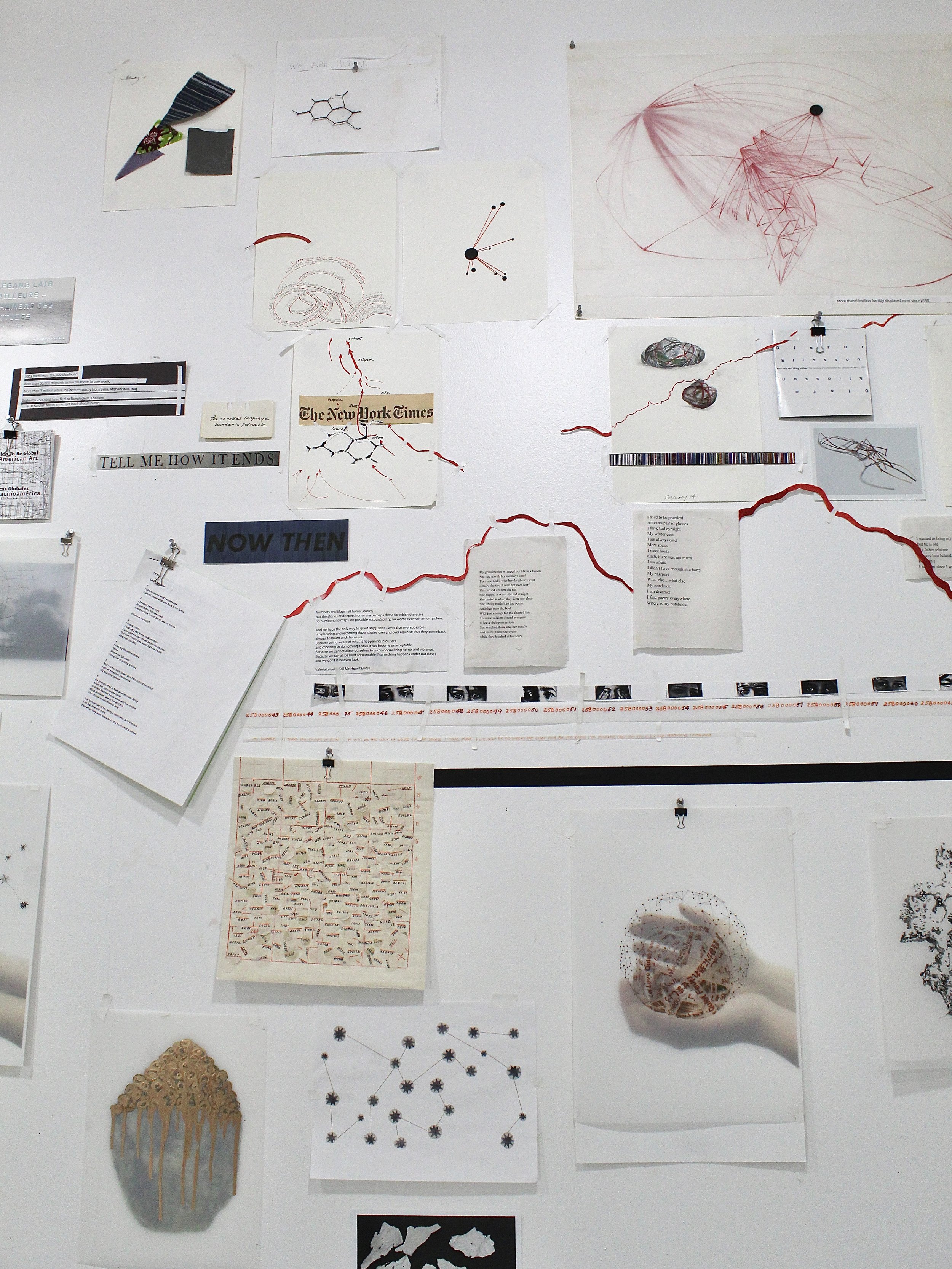

STUDIO PRACTICE

“Making work in the solitude of your studio, you try to be as authentic as you can with your work. In the studio I'm making work that shares my story and knowledge. But I hope the work extends beyond my own story to relate to a broader audience. The story of migration is a global issue and includes your family's lineage story as well.”

A visit to Wu’s Fort Point studio will sustain your need for beauty and experimentation and intellectual curiosity for weeks. Over here — in-process moon drawings. Over here — experimentations with new data visualizations and gilded tea bundles and on this wall drawings for new lantern shapes. She makes ceramic rocks indistinguishable from their natural models and accordion notebooks filled with minute, precise, temporal drawings. She stores bundles for use in future installations and hangs drawings to spur ideas for new work.

In “Playing to the Gallery,” Turner Prize winning artist Grayson Perry notes that “It’s a great joy to learn a technique because as soon as you learn it, you start thinking in it.” Wu thinks in data visualization. She thinks in collecting, transforming, expanding, detailing, bundling and mapping. She thinks in calm, careful precise methods, collecting hundreds of stories to counter disregard for cultural differences, mining data to record truths of human experience and tracing history to set records straight. As artist Nick Cave said, “Art has a way of bringing to you the things you need to know.” Art helps guide us through life. Thanks to Yu-Wen Wu, we have an enduring map.

Yu-Wen Wu is represented by Praise Shadows Gallery in Brookline, MA. Upcoming exhibitions include: Mother Lode: Materials and Memory (curated by Goodman Taft) at the James Cohen gallery opening June 20, 2024 and a solo show at Praise Shadows Gallery, September, 2024. She is the artist in residence at the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum this fall and will be creating the 2025 facade.