Yes April Bey, We Will Watch You Win

Frieze LA bore a heavy responsibility this year. The annual art fair was scheduled to open in Santa Monica only weeks after wildfires ravaged Pacific Palisades and Altadena, killing at least 30 people and claiming the homes and studios of dozens of artists. Frieze opened with the goal of supporting the city and its arts ecosystem, but lingering doubts remained: was it right to attend an art fair while people sifted through the ash of their homes five miles away? The show needed to demonstrate why art matters, and how it can extend a hand to those suffering, pulling them up with visions of solidarity and hope.

April Bey, “We Will Not Apologize for Being the Universe; Our Own Constellation. Don’t You Know Light Lives in Dark Places Too?” 2025. Jacquard woven textiles, sherpa blanket, giant clothespins, beads, 84” × 240”. Vielmetter Booth, Frieze LA 2025.

Vielmetter Gallery's exhibition of new work by April Bey was powerful enough to staunch the sting of guilt prickling attendees’ skin under their overthought art fair attire. With Bey’s installation, Vielmetter didn’t just answer the moment, it showed what it means to trust audiences to embrace the boldness and complexity such a moment requires.

Many galleries served up the same old thing, but Vielmetter staged a response addressing themes of care, climate, inclusion, technology, and Black and queer joy. By creating a vernacular mashing up everything from African mythology to cult films from the 1960s to internet memes, Bey delivers resonant meaning while achieving something hard these days: making us smile.

Vielmetter Gallery’s April Bey show at Frieze LA 2025. Installation view. Photo courtesy Aptil Bey Studio and Vielmetter Gallery.

Bey’s booth was a surreal cocoon of color, texture and curious portraiture. Eight mixed media works transformed peach and green walls into portals to another world. Emerald faux fur covered the back wall on which hung a monumental tapestry held by fur-covered clothespins, fringed in plastic beads. Entitled We Will Not Apologize for Being the Universe; Our Own Constellation. Don’t You Know Light Lives in Dark Places Too? (2025), the piece unites four portraits of serene Black women wearing futuristic tops and holding lambs. Their unblinking eyes, framed by afros, peek out from silk hair wraps, which may or may not be helmets. They seem to know something we don’t.

On an adjacent wall, four 36” x 24” collages mixing leather, crushed velvet and sequins, featured men surrounded by sunset-colored flowers, holding bears who (like the men) stare directly at the viewer. In A Fly Perched on the Scrotum is Gently Nudged off, NEVER Struck! (2025), the hunky sitter eyes the viewer while clutching a baby polar bear. The bear and his shirt, in leather, are hand-stitched with metallic thread into the crushed velvet, here taut, but in the three adjacent pieces, crinkly. Everything is real but not real, the layered material suggesting layered meanings and significance.

April Bey, “A Fly Perched on the Scrotum is Gently Nudged Off, NEVER Struck!,” 2025

Leather, crushed velvet, brocade fabric, metallic sequins, with metallic thread on stretched canvas

36" x 24". Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Brica Wilcox.

The portraits are complicated by machine printing and AI manipulation, giving them a kitschy aspect, especially when compared to the work of other contemporary textile artists like Diedrick Brackens or Bisa Butler. Into the machine-woven ground, hand-stitched segments in satin and leather add a sculptural element. This juxtaposition is signature Bey, as are the dreamlike colors which reference Junkanoo, the Bahamian carnival, and the confrontational titles which break the fourth wall. A heralded past show was titled, “Will You Watch Me Win?”

April Bey, “When Nobody Cared You Cared for Me, They Say You’re a Conspiracy,” 2025

Jacquard woven textiles, with hand-sewn fabric and sequins, beads, 80" x 60". Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Jeff McLane.

April Bey is an interdisciplinary artist and educator who grew up in the Bahamas and moved to the midwest as a teenager. She studied design in college and is now a tenured Design professor at Glendale Community College. Her body of work includes textiles, paintings, collage, public art and installations. Influenced by and borrowing from speculative futurism, internet culture and design, Bey investigates entrenched narratives around Black and queer identities and envisions paths toward resistance and liberation.

I spoke with the artist over Zoom in March and had the rare privilege of visiting her Los Angeles studio earlier this month.

What made the Frieze show so important for the moment was the way Bey’s surreal/idealist works are both portals to another world and mirrors of our earthly one. She invites us to imagine a better existence while confronting us with our divisive reality. “To me, Afrosurrealism serves as a warped or distorted mirror—it shows you the present but a warped and distorted present, whether it is fantastic, joyous, tragic, or dark.”

Raised in the Bahamas with a close extended family, Bey was allowed to roam free during summers at her grandmother’s family island house. Her work is influenced by the natural world she explored during these times, as well as alone time she used to read. Bey’s narrative influences are vast, including science fiction, speculative futurism, fan culture, pop culture, African folklore and the internet. She has depicted herself as “a Black, multiracial, multicultural, nomadic, queer femme that shifts and morphs every second.”

“You’ve got to make your own worlds. You’ve got to write yourself in.”

A self-described blerd, (Black nerd), Bey grew up reading everything she could get her hands on, including the banned Harry Potter books which had to be smuggled from friend to friend. She developed her deep love of fantasy from her father, a Trekkie. At a pivotal point in her childhood, he told her a story: they were not from Earth, but had been sent from another planet to observe and report back. In that way, the racism and sexism she learned about as a child could not hurt her in the same way. He created a buffer, a distance, which has helped her “report back” through her art.

That proud way of moving through an often unfriendly world laid the foundation for work that portrays the ideal and the aspirational rather than Black despair, which she says has been depicted enough. Her father’s story became the inspiration for a post-colonial utopia she has created over many years called Atlantica.

April Bey, “If You Want It It’s Mine You Can’t Stop Me,” 2022. Woven textiles, sherpa, glitter, resin, metallic thread, acrylic paint on canvas, 48 × 36 inches.

The works presented at Frieze LA—as well as the Armory Show 2024, Art Basel Miami 2024, the Union for Contemporary Art and The California African American Museum, among others, feature Atlantican characters, environments and worldview. Atlantica has no pain and no discrimination. Enter through magical blue holes—portals in Earth’s oceans. Shake glitter from your hair for currency.

“Atlantica is every inconvenience I have on Earth erased. You’re letting me sit at the table, and by the way, I brought snacks. Do you have a houseplant? If you have a houseplant you can come. Atlantica is designed with everyone in mind… you can be smoke if you want to. Or a thought,” Bey told me.

“We need not to be let alone. We need to be really bothered once in a while. How long is it since you were really bothered? About something important, about something real?

”

In her current work, two movies: Barbarella and the 1966 version of Fahrenheit 451 directed by François Truffaut, influenced her. The signature faux fur comes from Barbarella and many stylistic elements were influenced by Fahrenheit 451. “What I like about both movies,” she said, “is they keep the aesthetic of the time period. You can tell late sixties, but they are also dreaming about the future. When we look at relics or old things, we just believe. I like that authority that relics [hold for] present day people. That’s why I do tapestries. They look old, like a fresco or something that's been in a castle.”

Her juxtapositions show us our follies. Her embrace of kitsch and low brow materials fly in the face of colonial norms of what constitutes “real” art.

April Bey, “Creamy Chris,” 2013. Hair relaxer, oil paint.

Octavia Butler, Marlon James, N.K. Jemison and some other favorite authors model the experimentation Bey brings to her practice. Play is very important. She constantly tries new materials and tools, admitting she gets bored if she keeps doing the same thing. Early works experimented with hair relaxer, which she and her friend called Creamy Crack. Creamy Chris, for example, was a reaction to Chris Rock’s 2009 documentary Good Hair.

In her large LA studio, many works are underway at once. During my visit I witnessed experimentation with at least three new techniques for works in progress. For example, she showed me a new tufting gun and some of the experimental ways she was using it, calling to mind the work of Simone Elizabeth Saunders. Bey explained that she didn’t like that the floor of her Frieze show was bare. She was looking for ways to make the floor part of the portal to Atlantica. She is considering additional immersive elements for upcoming shows: Atlantican culinary experiences and libraries. The world continues to expand in her imagination and her practice.

Much of Bey’s work features Colonial Swag. As she described it, “Colonial Swag is our satire brand. It’s us making fun of Earth. We take earth’s racism and all the crap here, and that’s what we use to make our products. ”

Bey wants to decolonize every space. An upcoming series will include Colonial Swag school uniforms. She explained, “We see that you have to wear uniforms here, so we want to do that, but we’re going to do it better.”

Her Bahamian public school maintained a strict uniform policy, a remnant of British colonial rule. Bey traveled home to Nassau to the very uniform shop where she used to get her uniforms, still owned by the same woman, and brought samples back to Los Angeles. On Atlantica the uniforms are bound to be more flamboyant, forgiving and freaky than they were for her on Earth. “I’m going to do a whole photoshoot: ads, tapestries and stuff. A whole photoshoot of models wearing [uniforms]. I’m making back to school ads like Target does. Me addressing the uniforms as an adult now is different. The power dynamics are different now.”

April Bey, “COLONIAL SWAG: Bitch I had to Pay Myself Twice,” 2023. Jacquard woven textiles, with hand-sewn fabric and sequins, 80” × 60”.

Bey’s community building skills deepen the cultural significance of her practice. She holds public photo shoots and says most of the people who volunteer to be photographed are fans of Atlantica. They are immersed in the world. “So many people ask personal questions when I give talks. The Q&A is usually as long as the talk.” She has to reiterate that on Atlantica there is no race and no gender. “There aren’t really binaries that exist to limit people,” she says. “Skin in and of itself is just us copying and being cute. How cute that earth still has [race]. We [Atlanticans] gave that up millions of years ago.”

April Bey “I Have a 2 Inch Dick with a 4 Foot Swing,” 2024 Armory Show. Jacquard woven textiles, with hand-sewn fabric and sequins, beads. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles Photo credit: Jeff McLane.

April Bey, “Is Somebody Gonna Match My Freak? Is Somebody Gonna Match My Nasty?!,” 2024 Armory Show. Jacquard woven textiles, with hand-sewn fabric and sequins, beads. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Jeff McLane

Bey uses AI to manipulate her photos, adding stylistic elements and layers. The purposeful use of technology to create idealized versions of her characters speaks to selfie culture and the Kardashian effect: social media’s normalization of increasingly extreme beauty standards. By depicting unapologetic acceptance, compassion and care, she counters this standard, exhibiting strength in softness.

“A lot of us are flipping the script and saying the more tender you can be and the more compassion you show, the stronger you are. Sort of like a spider’s web.”

Equity in Collecting Program

When her work began commanding high prices, Bey worried that people she wanted to own her work wouldn’t be able to afford it. She also worried that the wealthy collectors who could afford it would flip it. The solution is Bey’s Equity in Collecting Program. She told me, “The reasons I couldn't afford the work are mostly related to my marginalized background and my lack of money. I’m also thinking about the people who made my career possible: women artists, historians, art professors, university and college art gallery curators, the woman who wrote my first LA Times article—none of these people could afford to buy my work.” So she created an application with the same criteria as Section 8. A supplemental discount is applied to the price, acting “as a leveling agent to provide access to potential collectors otherwise excluded.” She lists who she means here, including emerging artists and curators, women of color, LGBTQIA2S+, Indigenous people, single parents, a person with disabilities and recipients of federal assistance programs.”

Bey extends a hand to those she knows have it hard, pulling them up with opportunities for solidarity and hope. The program sells out every time.

April Bey, “COLONIAL SWAG: If You Meet Me as a $100 Bitch Me Supposed to be a $150 Bitch by Next Week” 2023. 2023, Jacquard woven textiles, with hand-sewn fabric and sequins, 80” × 60”.

April Bey, “I Will Never Ask ANY OF YOU For Respect, I Will Demand It” 2023. Jacquard woven textiles digitally designed, crushed velvet, glitter, resin, metallic thread, on panel. 60" × 48”.

From the ash of California’s recent fires, determined new life will bloom. Artists are the lights that guide us out of the darkness again and again. Angela Davis wrote that “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” In order to work toward a better collective future we have to believe, really believe that that future is possible. April Bey makes me believe.

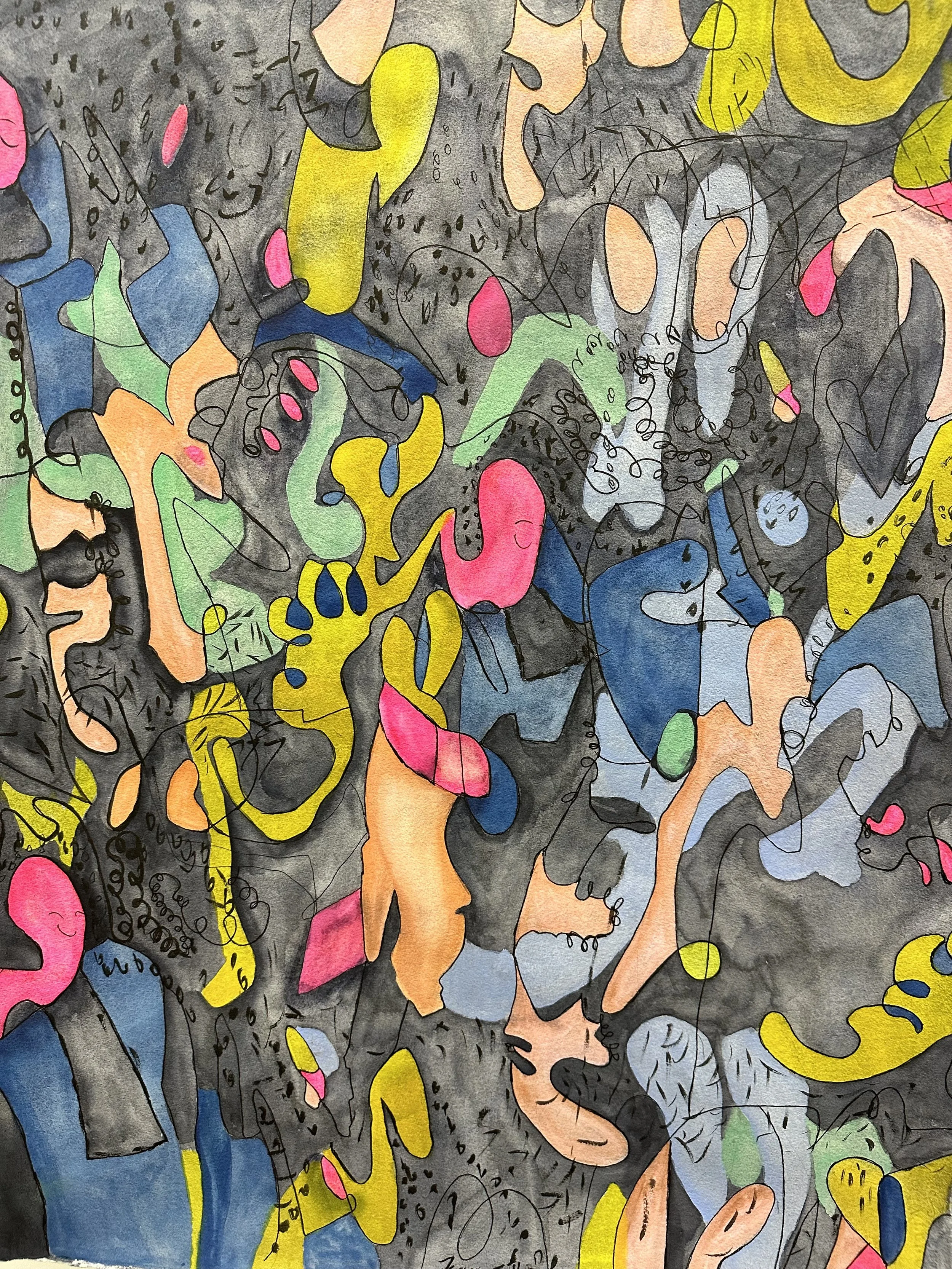

Cover Image: April Bey, “Did I EVER Ask You for Anything? DID I EVER ASK YOU FOR ANYTHING?!? I NEVER ASKED YOU FOR ANYTHING, NOT EVEN YOUR SORRY-ASS HAND IN MARRIAGE,” 2024. Jacquard woven textiles, with hand-sewn fabric and sequins, beads. 80" x 60." Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo credit: Jeff McLane