"The Procession" Captures the Ebullient Cacophony of Life

On Tuesday night the ICA Boston celebrated the opening of Hew Locke’s 140 figure installation, “The Procession,” at its East Boston exhibition space, The Watershed.

The Watershed show marks the North American debut of the Guyanese-British artist’s hugely ambitious project, originally commissioned in 2022 for the Tate Britain’s Duveen Hall. “The Procession,” co-curated with Locke’s partner, curator Indra Khannais, and organized in Boston by Ruth Erickson, ICA Chief Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs, and Anni A. Pullagura, Consulting Assistant Curator, is compellingly hard to classify. The installation comprises sculpture, textile design, painting, ornamentation, accumulation and assemblage, and almost feels like a performance, even though the statues don’t physically move.

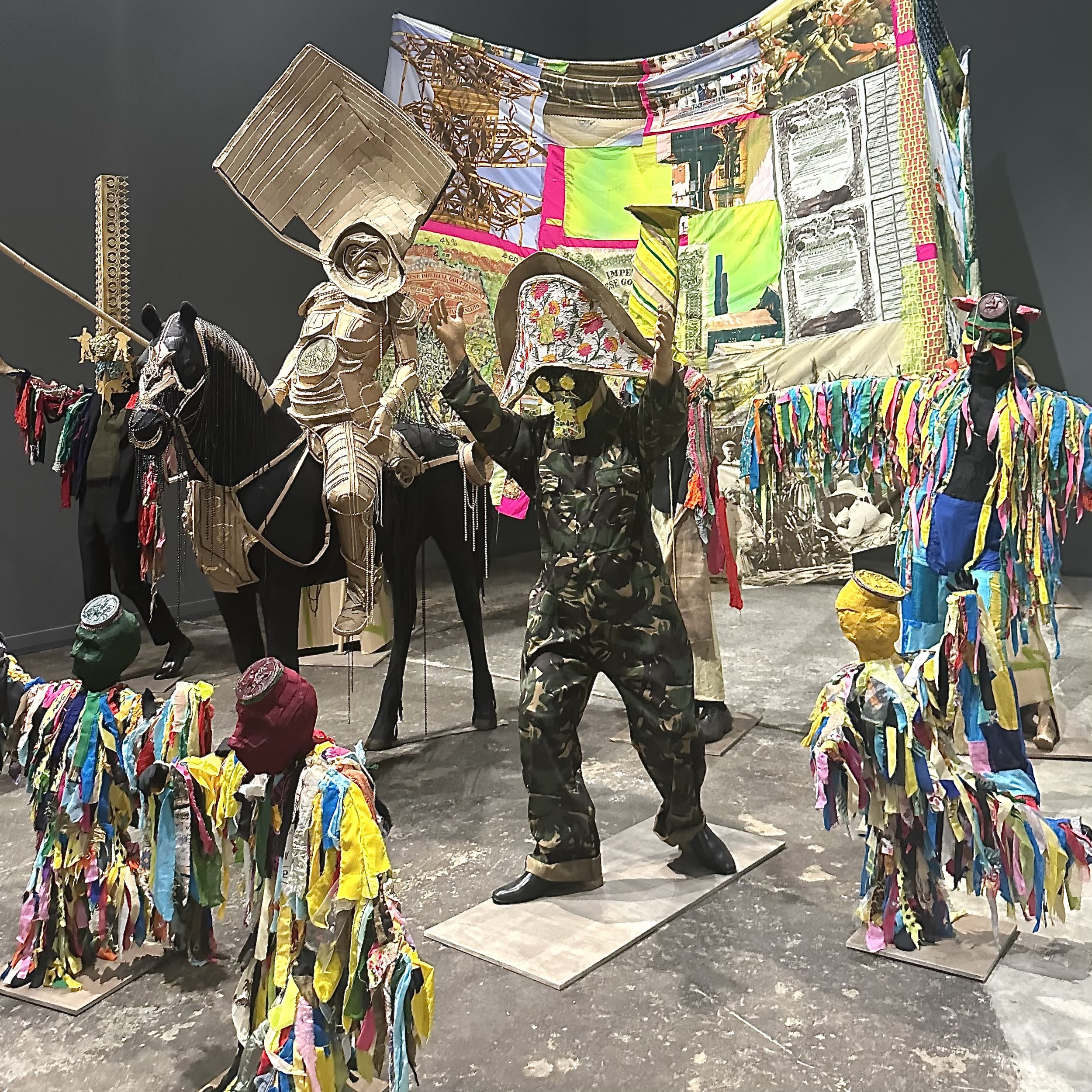

When you first enter, it’s hard to know where to look. The sight is dizzying, you get a contact high from all the eye candy. Like a teeming visual poem, “The Procession” greets you with a cast of 140 unique, mysterious, outlandish figures propelled toward some unseen collective goal. And the work fills the massive, open space of the Watershed like a flood of color, pattern, story and texture.

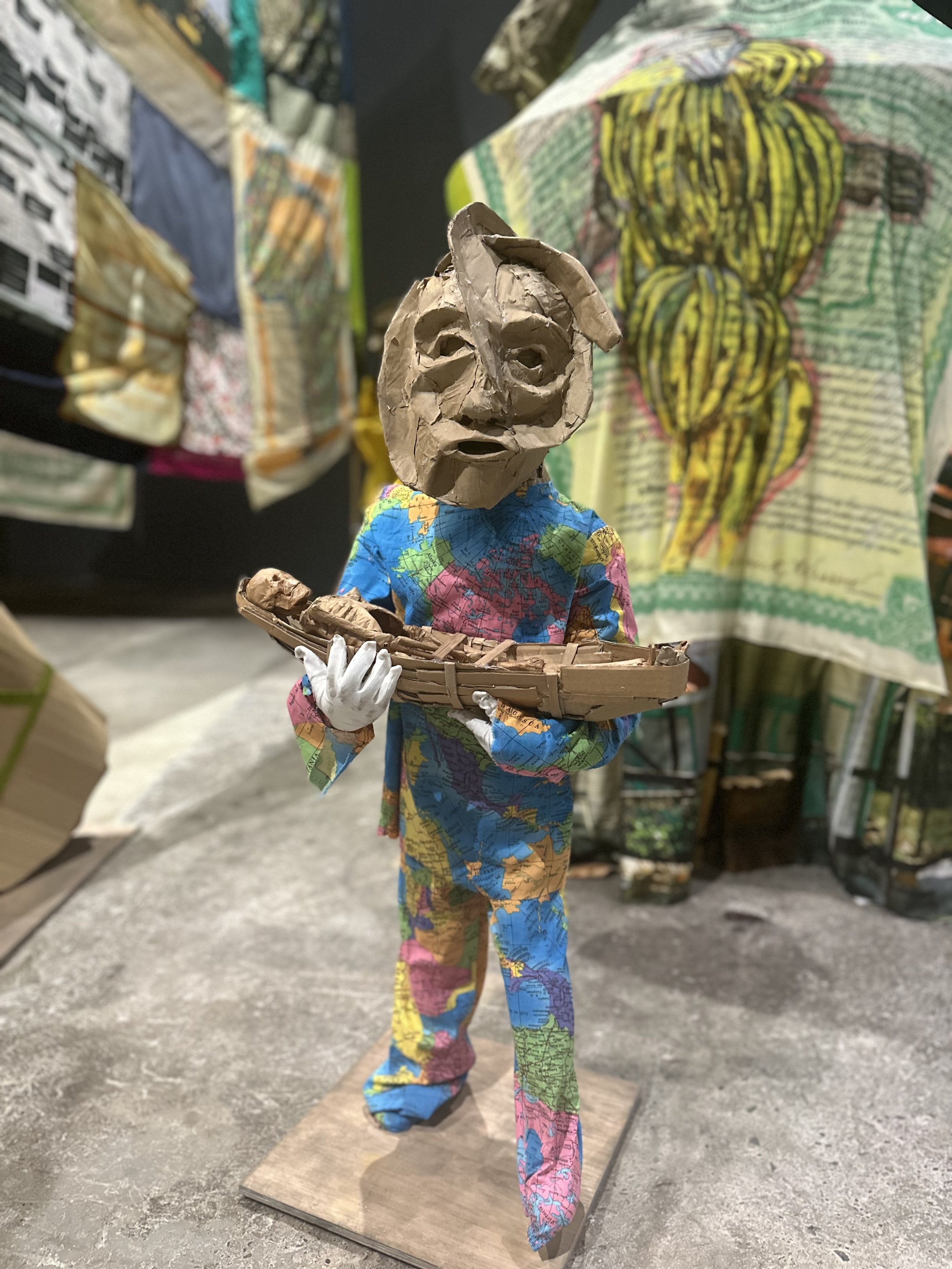

Most of the figures in “The Procession” are created from a base of cardboard, a material the artist has described as comforting in its familiarity and representative of the thematic contradictions in the work. Cardboard holds up when asked to bend, fold, wrap, hold; but disintegrates if it gets wet. Against the riotous colors of each figure’s design, the cardboard offers a blank slate, a baseline skin tone or building-off-point on which Locke layers carefully chosen and historically resonant objects and symbols as well as fabric of his own design.

With protective headpieces made from rags and burlap bags hanging from their horse’s saddle, some resemble refugees fleeing violence. Some don formal regalia or pressed suits and black dress shoes, medals weighing down the lapels of their jackets. Some are literally dripping in pearls, overwhelmed by wealth signifiers. Everywhere are flags, staffs, crowns and wildly elaborate headdresses. Occasionally a figure will call to mind Dio de los Muertos, hip hop dancers or even, chillingly, the Klu Klux Klan. Everywhere is a uniquely dilapidated, lavish grandeur.

Locke’s career has been noted for its tendency toward hybridity and excess. That could be explained partly by his self-described obsession with “heraldry and Britishness.” The theme of colonialism runs through the entire installation, that Britishness is not mainland so much as conquered territories abroad, (think once cosmopolitan cities like Kolkata [Calcutta]).

The figures range in size — many adult human-scale, some small (children? sprites? ghosts of former selves?), some intimidatingly tall as if on circus stilts. The circus is a reference, but a more important one is Carnival, that global celebration of cultural heritage practiced everywhere from Rio to Quebec, Barbados to Trinidad and Tobago. Whether a pagan festival celebrating the arrival of spring or a Christian one promoting indulgence before Lent, Carnival revelers get to let go of social norms and class distinctions, wearing masks to allow them to become someone else for the duration of the festivities.

But if you imagine “The Procession” to be a representation of some massive moving street party, a closer look reveals the hard historical truths these figures wear on their bodies, like skin scarred by fire. Locke makes his own fabric and many of the figures are dressed in or holding flags made of fabric bearing images from his body of work. These include colorful paintings on original antique share certificates of European companies in colonized countries, which he views as a window into the movement of ownership, affluence and power; and photographs of dilapidated houses sinking into flooding landscapes, part if an ongoing series started in 2013 in which he paints with acrylic and ink on c-type photographs. There are also photographs of plantation slaves and methods of slave counting on flags and clothing throughout the installation.

“We need to not be afraid to look at certain histories. History is messy - more messy and more complicated than people think. And I am a fan of complication.”

Locke is interested in the power of artifacts used to illustrate cultural identity. Ethnographic objects, patterned fabric, symbolic medallions and medals, jewelry, animal pelts (faux), sashes, devil-like horns, veils and baggage decorate his figures. These are examples of what Locke calls “lazy cliches,” blunt shorthand used to sum up national identities, classes, ranks and cultures.

Some symbols stretch up and back through history. Crude gas masks call to mind the outdated Soviet issued masks worn by Ukranian soldiers facing Russian drone attacks, Syrians attacked with sarin and mustard gas in the Syrian civil war, or soldiers in WWI. A carved palm tree covers the missing face of a figure dressed in a cheap mass-produced red sweatsuit, signaling the damaging global effects of fast fashion, from deforestation to child labor. Small figures trudge along carrying signs of death - pearl encrusted skeletons, boats carrying the dead, a deathly figure dragging scales of justice. Unlike revelers at Carnival, none of these are dancing. Serious expressions play on the faces that don’t wear masks. Vacant eyes search for a better tomorrow.

As the Tate Britain described it, Locke’s procession of figures asks us to “reflect on the cycles of history, and the ebb and flow of cultures, people and finance and power.” It also, like all Locke’s work, considers the question of public memory and how these types of symbolic images impact the way people settle difficult histories in their consciousness.

To experience “The Procession” is to feel you are in the middle of a movement, a participatory alliance, a protest. We could be marching for #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, Abortion Rights, Gun Control, Civil Rights, the Vietnam War, or from Selma to Montgomery. It could be the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests or a Rebellion of the Poor in South Africa. It could be a Roman army parading, exhausted but victorious, from a faraway battle, or the Haitian Revolution, the most successful slave rebellion in history.

This line kept going through my head as I took it in: the whole world is in this room.

It’s powerful to visit the show during a time when students are exercising their right to protest in response to the war in Gaza. And soon we’ll watch athletes from across the globe walk together carrying the Olympic torch for the Opening of the Summer Games in Paris.

Reflecting on life’s absurdity, Camus said, “There is no love of life without despair of life.” “The Procession” asks us to confront our mortality and absurdity while at the same time celebrating the ecstasy of human existance.

“I want to bring people beautiful objects with awkward histories, and smaller objects easy to walk by, that are just as compelling when you stop and look. There is a fascinating story hidden in plain sight, here and in many other museums across the country.”

“The Procession” reflects the chaos, complexity, color and creativity of life, memory and history. Despite their differences, the figures in Hew Locke’s work all face the same direction, a reflection of Locke’s careful optimism and a comfort to all who see it.

“[Locke is] a master at accumulating and assembling quotidian materials to create art objects that also serve as uncommon altars and shrines to our past… Floating on this tide are scraps and treasures from our shared histories which have left indelible imprints on our national narratives, even as we erase them from our conscious thoughts...”

Jill Medvedow, Ellen Matilda Poss Director of the ICA Boston toasts the artist on the occasion of the opening of his installation “The Procession” at the Watershed in East Boston.

The ICA Watershed is located at 256 Marginal Street in the East Boston Shipyard and Marina. It is open from 11am to 5pm Tuesday through Sunday.

All images, Robin Hauck.