Surface Scars: The stunning artwork of Evelyn Rydz

by Robin Hauck

What is native; what is not native? What and who becomes native over time?

Artist Evelyn Rydz explores these and other questions in her diverse body of work. Raised in Miami to a Cuban father and Colombian mother, Evelyn grew up along the southernmost coast of the US, just 330 miles across the mix of Atlantic and Gulf waters from her father’s native land. Working in photography, drawing, site-responsive installation and participatory community events, Rydz grounds her practice in field study and research. From gathering detritus on beaches and riverbanks to studying individual specimens through jeweler’s glasses, Rydz ponders the artifacts’ personal and political meanings, and invites us to do the same.

Oceanfront. Pencil and Color Pencil on Drafting Film, 18" x 72", 2014

Can objects’ surfaces show evidence of what they have experienced?

When she moved north in 2002 to pursue her MFA from Tufts School of Museum of Fine Arts, Rydz began considering the movement of other things up the coast and the implications of that movement on identity, adaptation and resilience. Her always-evolving body of work addresses urgent issues on a global and local scale: as a global community how do we address the catastrophic amount of plastic waste caught in our oceans, moved around the global conveyor belt and washed up on international coasts? What are the actual environmental benefits of local clean up efforts? And how do we treat neighbors who have come from somewhere else? As citizens in all countries consider issues of immigration, displacement and identity, how do we distinguish individuals from groups, unique beauty from collective stereotypes?

“In my projects... I aim to amplify and foreground what is out of sight, explore the familiar in unfamiliar ways, cultivate multiple perspectives, and draw connections between everyday individual actions and lasting cumulative impacts.”

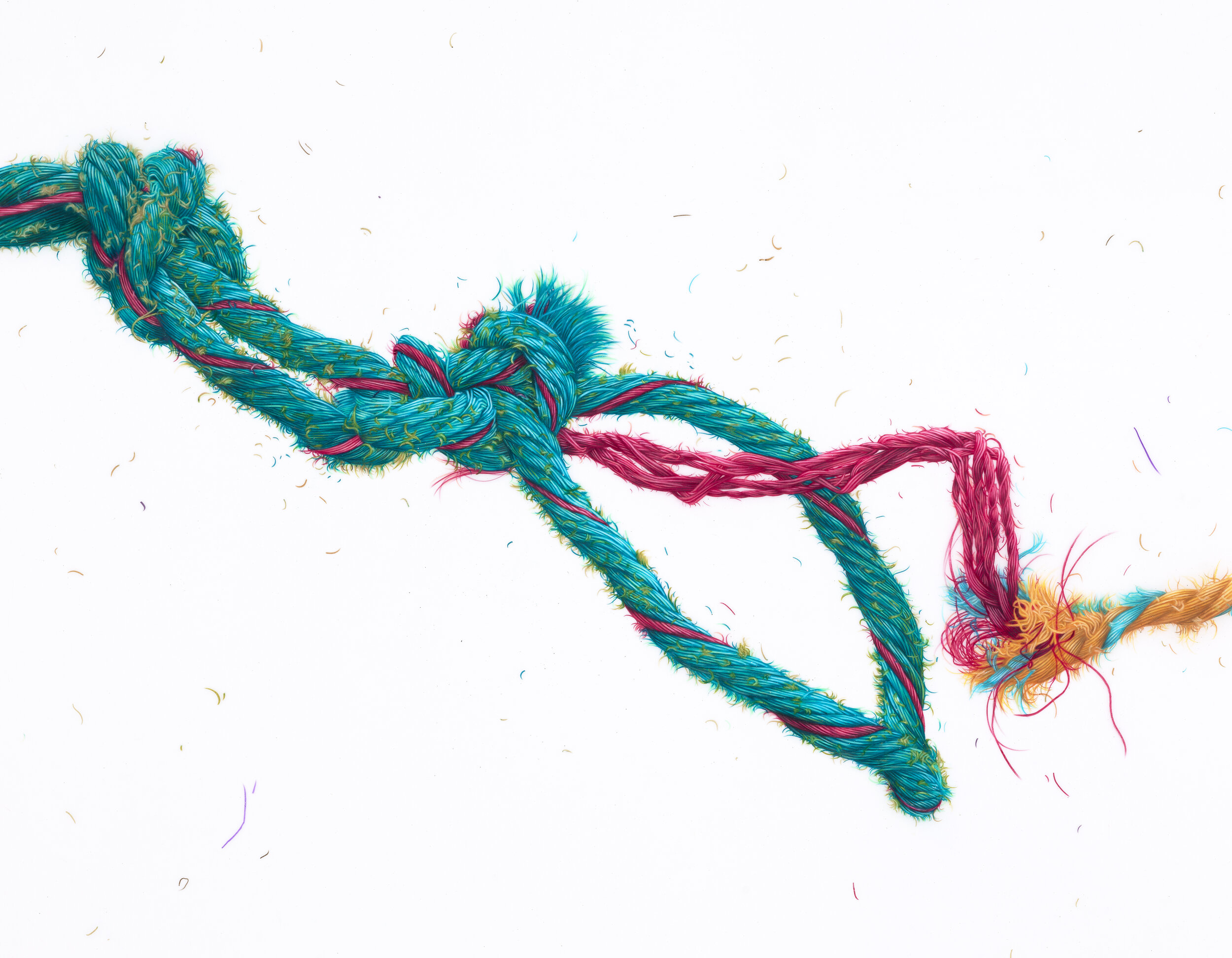

UNRAVELING & 1,000 YEARS

The catastrophic BP Oil Spill in 2010 inspired Rydz to investigate beaches up and down the east coast. The explosion and subsequent spill of the Deepwater Horizon rig dumped an estimated 210 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, though the full environmental impact of the spill is still being assessed. Rydz studied objects regurgitated by the ocean and collected rope and nets washed ashore from fishing vessels.

Two series of colored pencil drawings followed: Unraveling and 1,000 Years. Rydz explains she is interested not only in the objects’ relocation, but also their relationships and resilience. Documenting each artifact with microscopic accuracy, her drawings show the passage of time, the results of the long journey. They question how the surface can tell a story of the deeper impact of that journey.

The rope, like migrating people, lands on the beaches from far and wide. Rydz painstakingly splices rope pieces by undoing individual strands and weaving them back together, forming new combinations and reimagined objects. Stronger, she says, than tying knots, splicing is also more permanent. It involves weaving and twisting one into the other, a conjoining with stark symbolism. In her drawings every hair of the rope comes alive and from a distance the shapes they create are map-like, charting the path they’ve traveled.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates that it takes 1,000 years for a section of water to move around the globe, ocean to ocean along the “global conveyor belt.”

OCEANFRONT and POSTCARDS FROM KAMILO

In 2012 Rydz received Tuft SMFA’s prestigious Traveling Fellowship which allowed her to do her first work on the Pacific coast. She used the grant to visit Hawaii’s Kamilo Point, once a pristine stretch of white sand where locals salvaged beached logs for canoes. Due to its geographic location in a convergence of Pacific and equatorial currents, Kamilo Point, (also known as Trash Beach) is one of the most polluted on the planet. Kamilo collects trash from all over the world thanks to the currents, (and global consumption) and can often be buried under as much as 10 feet of debris, 90% of it plastic.

Visiting just after a volunteer beach cleanup, Rydz found a landscape of microplastics. It’s as if those plastic bits will still be around in a thousand years. Walking the littered beach, she was struck by the relationship of the parts to the whole, the story of each piece mapped onto the larger story of the beach and its burden. Her drawings abstract the pieces, flatten them and divorce them from a unique identity.

Objects land there from all over. Car parts, plastic bottles, tennis shoes, refrigerators, crates from fishing vessels, tennis ball, bits of baby dolls, packaging and furniture. They crowd the beach after their journey, all colors, all shapes, all with a long and traumatic story. Powerful metaphors for our global immigration crisis.

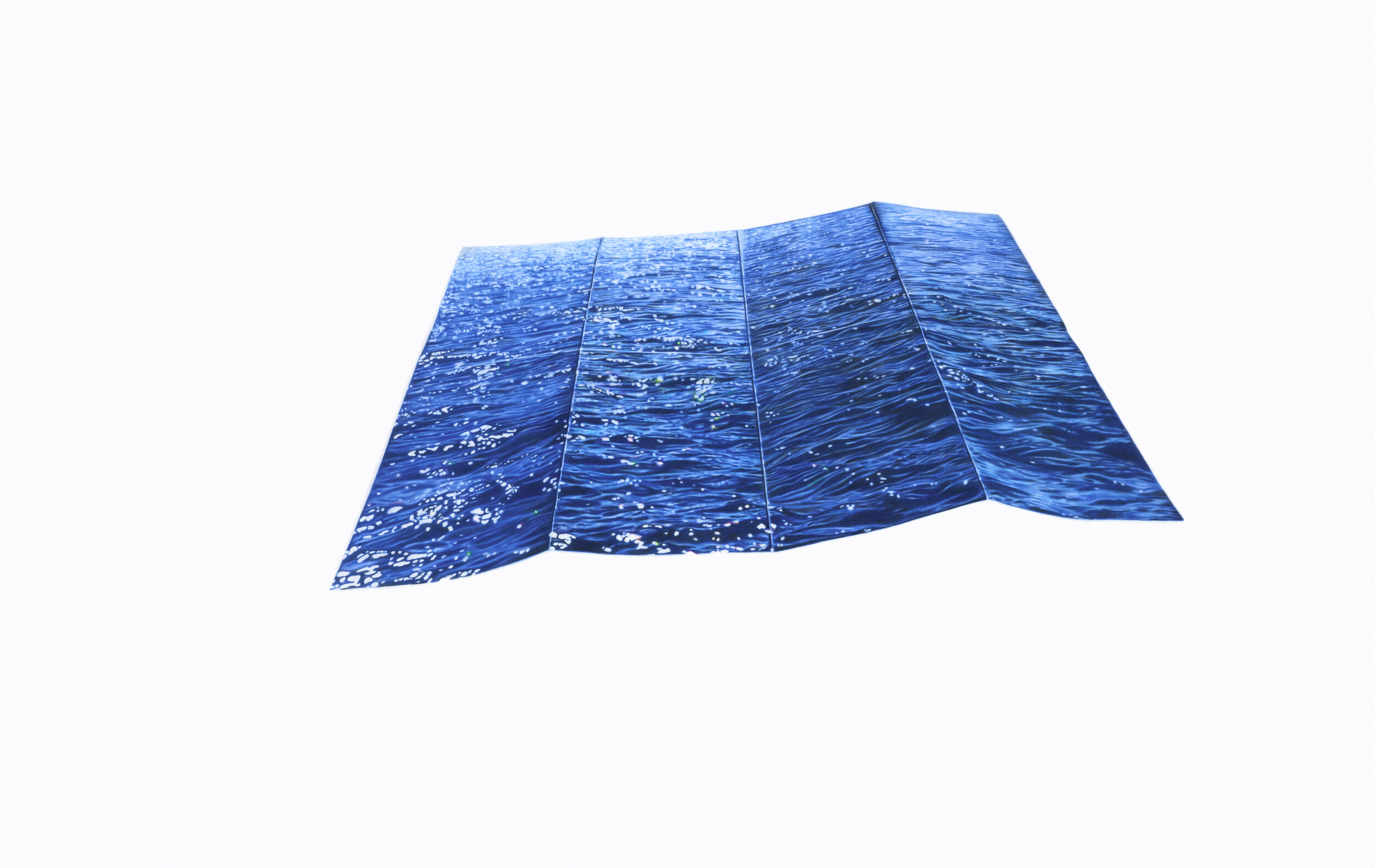

FOLDED WATERS

In 2017, Rydz received the prestigious Brother Thomas Fellowship, awarded biennially by the Boston Foundation. She used this time to investigate the “shifting territory of water.” Standing on a pier in Miami she said she was struck by the experience of “looking at Cuba, so close but so far.” Maps delineate territories, countries, boundaries across bodies of water, but how does that translate in the actual bodies of water, the water that moves on its own time across the globe, as part of the “global conveyor belt.”

Folded Waters contemplates patterns, oceans and the politics of belonging. Again working towards abstraction and cognitive distance, she took photographs of ocean water, printed those large scale and folded them according to boating maps. Again using jewelers glasses, Rydz drew the resulting compositions with colored pencil, capturing in painstaking detail every stroke of blue and flicker of light on the surface.

For an exhibition at the 13th Havana Biennial in Cuba, Rydz printed images on pigment print and folded it on the ground, topped with a piece of coral found on the beach.

THE MOUTH

Evelyn Rydz, The Mouth, Merrimack River Water, Concrete Pavers, Used Glasses, 2020

Eager to see her in action in the classroom (Rydz is also an Associate Professor at Massachusetts College of Art and Design) I recently crashed her lecture at UMass Lowell, part of the collaborative exhibit and series between UMass Dartmouth, UMass Boston and UMass Lowell called “Local Ecologies.”

In Lowell, the Merrimack River should be a source of recreation, natural beauty and - for over 600,000 area residents - daily drinking water. But due to overflow from six area sewage treatment facilities, the river is often polluted and unsafe. The Merrimack River Watershed Council reports that heavy rainfall causes overflow, (400 million gallons in a typical year) as the treatment facilities have not been upgraded. And we all know that climate change increases the frequency and severity of storms.

For her installation at UMass Lowell, Rydz collected river water from the mouth of the river, exactly where it meets the Atlantic Ocean. These waters have different chemical compositions, different histories, Rydz explains, having traveled different journeys. But here they meet and become one invisibly. She created a crystal open-mouthed map of the river’s mouth using glasses made in the region. The water filling each glass came from the part of the river it represents on the map. Some held dirt and maybe sewage. Some was clear.

In her lecture, Rydz addressed the relationship between science and art; both art and science majors attended. Both disciplines, she said, problem solve and ask questions. Both utilize a space of quiet contemplation - the lab and the studio. Both have a chance to offer new and different perspectives to local and global issues.

She asked the students the question, “Are we included in nature? We love it, but we abuse it.” She ended with the imperative to take action. As a collective, our small actions can make a big impact.

Rydz encourages the students to ponder her work as a lens through which they might discover different perspectives. Take a look yourself, make your own decisions, come to your own conclusions or rather just feel the inspiration to continue to look, consider and think without judgement.

Sitting in the sun on a grassy hill painting with river water and pine needle brushes, art student Jessica Kramer and science student Echo Heinze reflected on their experience living near the Merrimack River at school. It’s pretty if you don’t look too close, they said. You don’t want to look closely once you know what’s in it. But looking closely is exactly what Evelyn Rydz does and what she inspires us to do too.

Evelyn Rydz is represented by Ellen Miller Gallery.