Mother Water | Father Land: Elements, History and Hope at Prospect.5 New Orleans

The sky was so blue that day. As blue as water. As blue as the Gulf of Mexico or the Lake Pontchartrain of our dreams. Above us the sky was all fluidity, depth and spaciousness, but down on the ground Simone Leigh’s sculpture Sentinel (Mami Wata) spoke to tradition, ritual, power and hope. Not just “down on the ground,” but at a charged site where a monument to confederate white supremacy had loomed over New Orleans for 133 years.

It was the final weekend of Prospect.5, the fifth iteration of the New Orleans Triennial initially conceived to address the devastation of Hurricane Katrina on the city and its people. An eager crowd of artists, curators, neighbors, activists and reporters had gathered to watch the unveiling of Simon Leigh’s much anticipated work installed at the site where a Robert E Lee monument was removed in 2017.

Simone Leigh’s Sentinel (Mami Wata) under the almost 60 foot pillar on which the monument to Robert E. Lee once stood. Leigh chose to have her work installed nearer to the ground, closer to the people who would see it.

Simone Leigh

Sentinel (Mami Wata) is Leigh's answer to questions posed by the present moment: what kind of monument can address the wounds inflicted in the past and perpetuated by history? How can a work of art heal the trauma inflicted by one race on another? Can the strength represented by a female deity embraced by the African diaspora overcome the horror represented by a male Southern war hero embraced by ideologues?

Her sculpture stands tall, reaching gracefully to the sky, a water goddess entwined by a serpent. Mami Wata’s head is shaped like a ceremonial spoon, a status symbol in Zulu culture. Leigh is known for using domestic forms like jugs, bowls and huts in her figurative sculptures.

Prospect.5 Artistic Directors Diana Nawi and Naima J. Keith in front of Simone Leigh’s Sentinel (Mami Wata) 2021 at the site of what was formerly known as Lee Circle and the monument to the Confederate general.

The Triennial, which ran from late October 2021 through January 2022, was titled “Yesterday We Said Tomorrow.” All 51 artists invited to participate addressed the impact of the past on the present and the myriad ways art can act as a bridge. As LaToya Cantrell, Mayor of New Orleans wrote, “Prospect brings to the fore artists who challenge us to think about what could be rather than what is.”

Prospect.5 Artistic Directors Naima J. Keith and Diana Nawi and Executive Director Nick Stillman spoke at Sentinel’s unveiling, but the most moving dedication came from a local priestess. She described Mami Wata (Mother Water) as a powerful African deity, the mother of all waters. She shared that Mami Wata represents deep waters and deep emotion and ways to navigate them. She represents fluidity and how we flow through life, empowering deep healing for humanity. She shows us our power and all we can achieve, the priestess said, but she asks us to respect all waters and honor the depths of who we are. She brought Leigh’s work to life and sent us off with an assignment.

Like the gulf and lake water that surrounds New Orleans, both giving life and — especially since Hurricane Katrina — threatening death, our shared past seeps into our present experience informing our sense of self and place. These are the themes that connect the work of Prospect.5. I was there with VIA, the visionary art fund founded by Bridgitt Evans. With 51 artists exhibiting at dozens of venues, only a catalogue can capture the work in its entirety. Therefore what follows are some of my favorite highlights from Yesterday We Said Tomorrow.

Glenn Ligon

Glenn Ligon, known for his investigations and activations of language in his text-based paintings and sculptures, created six neon sculptures for Prospect.5 which mark the dates of the removal of seven confederate monuments in New Orleans. Mounted on the curved walls of a chapel-like space in the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the illuminated works reverberate with meaning, forcing us to remember not just the dates of the monuments’ removal, but their longevity, all the days the monuments stood in public places reinforcing white supremacist values. Ligon who has made neon date sculptures to commemorate the election of Barak Obama - One Black Day (2012) and his replacement by Donald Trump - One Black Day II (2017), upends notions of what constitutes a “monument” at a time when monuments themselves sit at the intersection of competing ideas of how and what deserves to be upheld as American “history.”

Glenn Ligon’s neon sculptures in a wing of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

EJ Hill

New Orleans is a city of neighborhoods, each with its own colorful character. One of Prospect’s defining features is its commitment to exhibiting work across many neighborhoods, requiring artists and visitors to traverse the city and recognize its refusal for easy characterization.

On the outskirts of town, in the area known as New Orleans East, a different kind of monument meets the sky at the entrance to the Joe W. Brown Park. Considering the ways Hurricane Katrina’s destruction indelibly impacted New Orleans’ Black neighborhoods, Hill adopted the closed amusement part Six Flags Jazzland as his muse. Erecting a bright yellow half wheel from which he suspended a seat from the Jazzland ferris wheel called The Big Easy, Hill calls to mind the circular, continual loop of hope and disappointment experienced by these communities post-Katrina. His work asks, what happens when a site of Black joy is destroyed? How does the city respond or not respond? Will the freedom to play ever truly be realized?

EJ Hill’s monument, Rises in the East, 2021 at Joe W. Brown Park in East New Orleans.

Sharon Hayes

Sharon Hayes’s video and performance work documents the real lives of real people in real places. Her 7-channel color video installation produced for Prospect.5, If we had had, 2021 was exhibited in the cozy Oxalis Bar on Dauphine Street in Bywater, shuttered since 2019. Mounted on seven walls throughout the space, the videos follow 22 queer and trans characters as they traverse New Orleans. Hayes' work viscerally activated the decommissioned space - as if the ghosts of former patrons were watching too, reminding us of such spaces not safe for subjects like hers. The possibility of their peace, ambition and joy remains ambiguous as their movements play out against the soundtrack of seven queer and trans performers singing karaoke. Rather than considering what follows the loss of a specific site of joy as EJ Hill did with Rises in the East, Hayes addresses the way political and social history impact the LBGTQ community’s present reality in the city and beyond.

Still image from Sharon Hayes multi-channel video work, If we had had, 2021 at the closed Oxalis Bar.

Dawoud Bey

Dawoud Bey with Los Angeles based art advisor Victoria Burns.

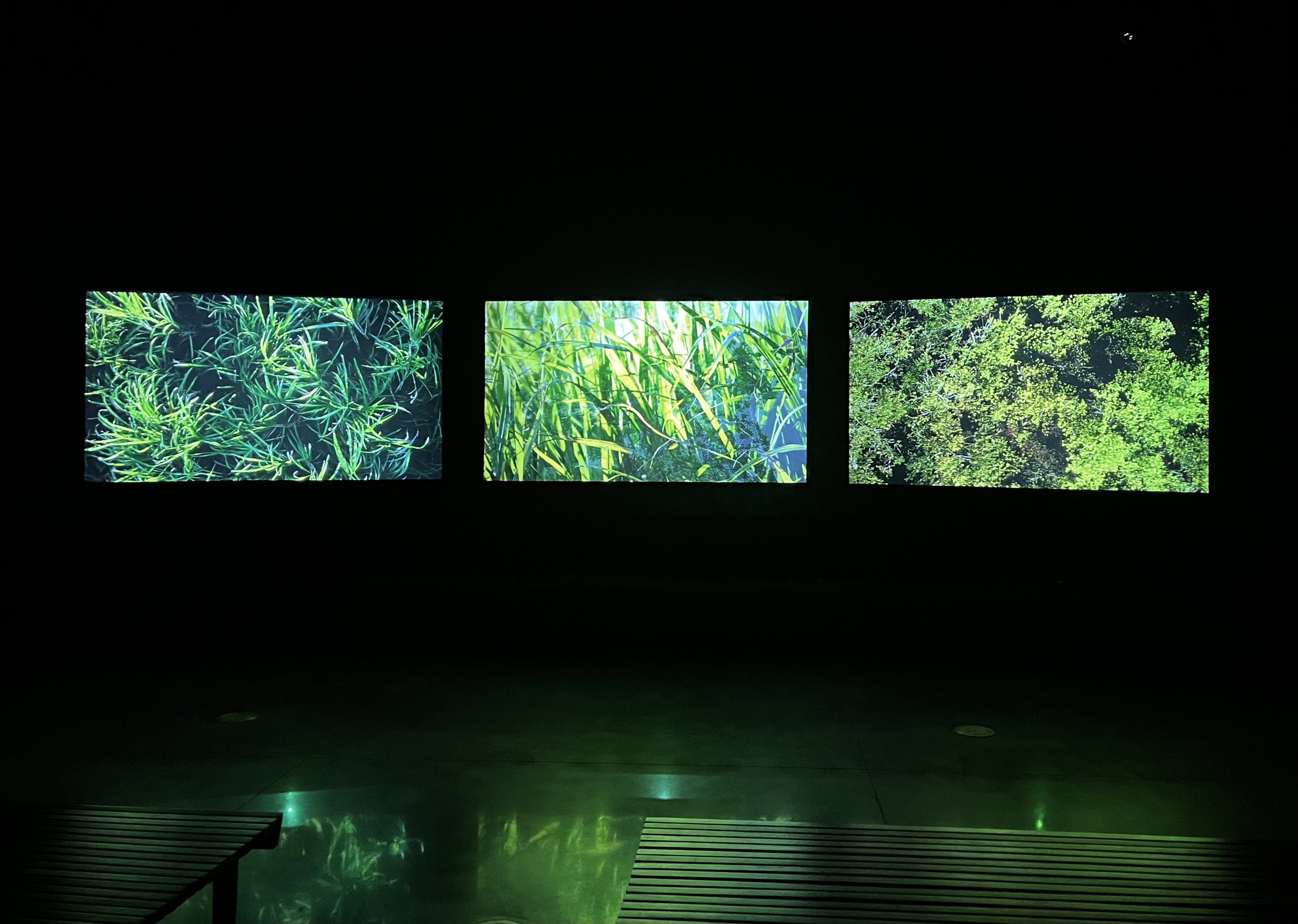

Can the land remember? Does soil hold on to blood? Do trees bear witness to acts committed in their presence - whether of love or hate, savagery or passion? In his haunting photo and video work for Prospect.5, In This Here Place, Dawoud Bey looked to the land, placing the viewer in proximity to the site of unthinkable atrocity. In This Here Place is a series of lush, velvety black and white photographs taken at Louisiana plantations.

The three channel video “Evergreen” was shot at Evergreen Plantation, where slave quarters still stand, testament to a violent past. From the cabins, ghosts of former inhabitants seem to linger. We feel them in the blades of grass, the sugar cane, the dropping limbs of willow trees. We hear them in the accompanying soundtrack by vocalist and composer Imani Uzuri.

Before the Civil War, New Orleans was the center of the United States slave trade – at one point as many as one in three residents was enslaved. Throughout Louisiana, many plantations which bought, sold and exploited slaves still stand. Bey asks the questions history resists, (“The Problem We All Live With,” to quote Normal Rockwell’s title for his painting of Ruby Bridges): how do we carry on without crumbling under the weight of such a past? How can history accurately record it? What now?

A still from Dewoud Bey’s three channel video work, Evergreen.

Antenna

Antenna is an independent artist-led organization based in New Orleans. One of seven satellite projects chosen by Prospect.5 to participate, (partially in response to criticism that Prospect has not included enough local artists), Antenna mounted a multi-disciplinary show featuring the work of 25 artists on the loaded subject of sugar. As Louisiana accounts for 20% of the sugar production the United States, sugar is big business and ripe for controversy in New Orleans. Throughout the show, curated by Denise Frazier and Renee Royale, artists addressed issues of labor, land, pollution, the plantation economy and slavery, impact on biodiversity, colonialism, disaster capitalism, camp and unhealthy habits.

Tau Lewis

If I had to choose one artist I was most excited to discover at Prospect.5, I would choose Tau Lewis. In the gallery at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art where Prospect.5 artists Glenn Ligon (see above), Willie Birch, Jennie C. Jones, Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Beverly Buchanan, Jennifer Packer, Welmon Sharlhorne, Katrina Andry, and the Neighborhood Story Project exhibited, Tau Lewis’s sewn assemblages stood out like petals on water.

They’re arrestingly beautiful to start - soft palettes of yellow and pink and unapologetically feminine. The hanging soft sculpture Delight especially enchanted me, a swinging figure of vague gender and species surrounded by floating petals is part of her recent series T.A.U.B.I.S. (the Triumphant Alliance of Ubiquitous Blossoms of Incarnate Souls). Lewis is self taught and her art addresses the meaning and memory of objects. Her works are often assemblages, deriving their power from the histories of other objects or materials such as recycled leather, bedding, clothing, cotton batting, seashells and more. Her interest in the past histories and journeys of her source materials reminded me of the work of Evelyn Rydz, who finds stories of journeys across waters in ocean microplastics and detritus. If trees and structures tell stories, hold memories and recall history in the work of Dawoud Bey, recycled, sourced objects do the same in Tau Lewis’s world.

A different way to bear witness one stitch, one piece, at a time.

Lewis’s work in the gallery, surrounded by shack and cabin sculptures by Beverly Buchanan.

Knot of Pacification, 2021 and Delight, 2020 both by Tau Lewis at the Ogden Museum.

While we were in New Orleans, the Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh passed away. His beautiful words from Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life seemed an appropriate sentiment for the spirit of Prospect.5 evoked by the title Yesterday we said tomorrow.

“Hope is important because it can make the present moment less difficult to bear. If we believe that tomorrow will be better, we can bear a hardship today.”

Parting scenes from New Orleans

Our group in front of Elliott Hundley’s epic collage The Balcony at The Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane.

Cover Image: detail of RaMell Ross Here 2012

*all photos taken by the author.