Writing History in Granite and Bronze

Shoes on the Danube Bank, photo: Robin Hauck

I remember coming upon the shoes in Budapest. As our group walked along the Danube, they appeared quietly, dozens of pairs, cast in iron. This was Shoes on the Danube Bank (Hungarian: Cipők a Duna-parton) the memorial to the hundreds of Jews killed by the fascist Hungarian militia, The Arrow Cross, during WWII. The work was conceived by film director Can Togay to capture the atrocities committed there: men, women and children forced to remove their shoes before they were shot so their bodies fell into the river. That memorial, more than any castle, lecture or tour, gave me a sense of Hungary’s pain. Once I saw the shoes, everything else made sense, including the constant sense of dread I felt while in the city. The shoes explain how the horrors of the past live on in Hungary’s present.

“Monuments are markers in time, erected in a present to tell future generations what we value, and perhaps what they should value too,” explains Dr. Raul Fernandez, Senior Lecturer, Boston University and designer of BU’s “Identity, Inclusion & Social Action” curriculum.

The word monument comes from the Latin monere ‘remind.’ Lest citizens forget, civilizations throughout time have erected monuments to mark important occurrences and honor influential figures. Many, like the shoes, commemorate rather than discriminate. But large scale public sculpture has also been deployed to promote ideological agendas and rewrite the past. Nowhere is this more evident in the U.S. than in the South, where hundreds of monuments were erected to celebrate the Confederacy.

Over the last decade, Confederate symbols in all forms, from monuments to street names, have been examined and debated with renewed fervor, reflecting shifting notions of American nationhood.

The Robert E. Lee statue removed from its plinth on Monument Ave. in Richmond in September, 2021. Win MacNamee, Getty images.

As observed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, “although some were erected… for reasons of memorialization, most Confederate monuments were intended to serve as a celebration of Lost Cause mythology and to advance the ideas of white supremacy… To many African Americans, they continue to serve as constant and painful reminders that racism is embedded in American society.”

Though activist group had been calling for removal for years, U.S. cities began to look seriously at this issue in 2015, when white nationalist and neo-Nazi Dylan Roof murdered nine congregants attending service at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC. Decommissioning continued in 2017, around the “Unite the Right Rally” in Charlottesville, VA and in 2020 following the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Rayshard Brooks.

Proponents of monument removal insist they act as unifying symbols for hate groups and right wing extremists and perpetuate white supremacy. Opponents argue we cannot erase history and monuments are important symbols of our country’s past. The impassioned debate sparked by this issue has put monuments at the very center of contemporary culture wars.

This is where artists come in.

“In these toxic times art can help us transform and give us a sense of purpose. The story begins with my seeing the Confederate monuments. What does it feel like if you are black and walking beneath this? We come from a beautiful, fractured situation. Let’s take these fractured pieces and put them back together.””

Kehinde Wiley, “Rumors of War” now installed permanently at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. Photo: Travis Fullerton.

Best known for his genre-busting portrait of President Barak Obama, Kehinde Wiley inserts Black subjects into settings and postures traditionally occupied by figures of white power and status. He was invited by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond to create a permanent work to occupy space at the front of the museum, close to Monument Avenue where a line of Confederate monuments once stood.

Richmond, once the capital of the Confederacy, has been in the center of the monument debate, and has removed a dozen confederate monuments and markers since 2017.

Wiley created “Rumors of War” after seeing a statue commemorating the Confederate general J.E. B. Stuart that was erected in Richmond during the rise of Jim Crow. His imposing version (27 feet tall and 25 wide, weighing 30 tons) features a young African American male, chin high and braids flying, commanding a muscular horse in a hoodie and Nike high tops.

Wiley’s overarching project is to almost quote the form he’s working in - medium, style, attitude - and embody it with ordinary people he meets in his travels. In this way he addresses the question of who gets to be memorialized, as well as appropriating and expanding artistic traditions for their McLuan-esque power (form+content=meaning). By adopting a familiar construct and subverting it with an unfamiliar hero, “Rumors of War” offers a powerful counter to the long history of problematic monuments in the geographical center of the debate.

What monuments a city erects and maintains says a lot about that city. Contemporary monuments and memorials must portray a breadth of worldviews, or at least not diminish or exclude perspectives outside the dominant.

Simone Leigh, “Sentinel (Mami Wata)” at its unveiling in New Orleans. The work is currently on view at Harvard Business School until 2027.

Consider Simon Leigh’s “Sentinel (Mami Wata),” unveiled during Prospect New Orleans in January 2022. In the shadow of the 60 foot pedestal which from 1884 to 2017 held a statue of Confederate General Robert E Lee, “Sentinel (Mami Wata),” offers a history erased by public art in the south, that of African diasporic traditions, myths and signifiers.

Unveiling the statue in what was formerly known as Lee Circle (now Tivoli Circle) in the center of New Orleans put it in dialogue with the absent Lee monument, adding a new chapter to New Orleans’ complex history.

Today “Mami Wata” can be viewed on the grounds of the Harvard Business School thanks to a contemporary art fund started by Bridgitt and Bruce Evans.

New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu commented on the decommissioned works: “These monuments stand not as mournful markers of our legacy of slavery and segregation, but in reverence of it. They are an inaccurate recitation of our past, an affront to our present and a poor prescription for our future.”

As evidenced by the violent Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville in which Nazi sympathizers and white supremacists rioted against the removal of a Confederate monument, the Mayor’s sentiments are far from universal. But not all those who oppose removal take to the streets or perpetuate violence. Many use the courts to fight these changes. Republican lawmakers in Alabama and North Carolina passed laws prohibiting the relocation or removal of monuments except under special circumstances. And the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) established in 1894, which has funded some 450 monuments to the Confederacy, has a team dedicated to fighting monument removal in the courts.

“As we continue to reckon with our colonialist and racist past and address present symbols and systems of racism, we look to artists to shine light on continued cultural and social injustices and envision equitable representations and commemorations for future generations.”

But what happens when controversial monuments are removed? Where do they go and can they have a second life as weapons of public education rather than oppression? Can artists really make a difference in such a widespread, political, economically significant issue?

Hamza Walker, of LAXART believes they can. Stepping into his role as Director of the contemporary art nonprofit one month after Donald Trump was elected president, Walker knew something ambitious and bold was required of his exhibition calendar. Along with The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (MOCA) and artist Kara Walker (no relation that they know of) he conceived of MONUMENTS, an exhibition in which decommissioned statues, removed from their geographic and ideological setting, could be considered, not just as propaganda for hatred and division, but as art objects. LAXARTS has invited artists to create work which speaks to, challenges and in some cases re-imagines monuments.

One of these artists is the multi-media art world mega-star Kara Walker.

Best known for her large silhouetted tableaus confronting racial crimes of the antebellum south, Walker has also produced groundbreaking large scale public projects. Her Hyundai Commission for the Tate Modern, “Fons Americanus” examined how monuments work to impact memory and the power of the ideals hidden in those memories. Her mammoth, sphinx-like installation ”A Subtlety, or The Marvelous Sugar Baby”, subtitled: “an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant,” (Walker is famous for her titles) filled the abandoned plant with a 35 ton sugar sculpture that spoke to histories of slavery, sugar production, sexualization of the Black female form and the politics of labor.

Anne Pasternak, President of Creativetime, which sponsored the work, explained, “Kara Walker is encouraging us to look at things that are so visible in our society that we wish were invisible… And it’s our belief that public art creates a space to engage in those difficult conversations.”

MONUMENTS will open in Los Angeles in 2025 and will include multiple artists’ work and multiple decommissioned Confederate monuments.

Lauren Halsey, “the eastside of south central los angeles hieroglyph prototype architecture (1)” 2023. The Roof Garden Commission, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Robin Hauck

Contemporary artists often respond to the public’s fascination with monumentality. Does the fact that it’s enormous or placed high above the viewer on a plinth inherently bestow a work of art with cultural significance?

“My interest was never about needing to recreate pharaonic objects or anything like that. It was more figuring out how I could appropriate some of the forms, so that they appeared antiquated but were actually contemporary, as a way to think about permanence in storytelling and to think about a collective Black future.”

Many would argue yes, it does, which is why it’s so important for artists to portray underrepresented themes, figures and ideas in public art.

36 year old artist Lauren Halsey considers this among other questions in her commission for the Cantor Rooftop at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (on view now through Oct 22, 2023). Monumentality was important to the ancient Egyptians, from whom she draws enormous inspiration, thanks to family members who immersed her in it. Halsey’s work references hieroglyphics, ancient Egyptian architecture and pharaonic symbolism, as well as the aesthetics of her Los Angeles neighborhood and Afro Futurism.

Her work remixes influences, images and symbols, “funkifying it” as she says, to reclaim lost histories and design powerful futures. Seen from the Great Lawn in Central Park, the columns and inscriptions of “the eastside of south central los angeles hieroglyph prototype architecture (1)” might appear to be the expected on Egyptian architecture. But Halsey has covered the entire building and columns with sayings, names, text and signage from South Central LA. The faces that adorn the columns and sphinxes are modeled on her own family.

After October, Halsey’s goal is to reconstruct her architectural monument in her own neighborhood and one day turn it into a community center. Her monument is, for her, a physical manifestation of future hope; a radical welcome for one and all to join in solidarity around pride of place and history.

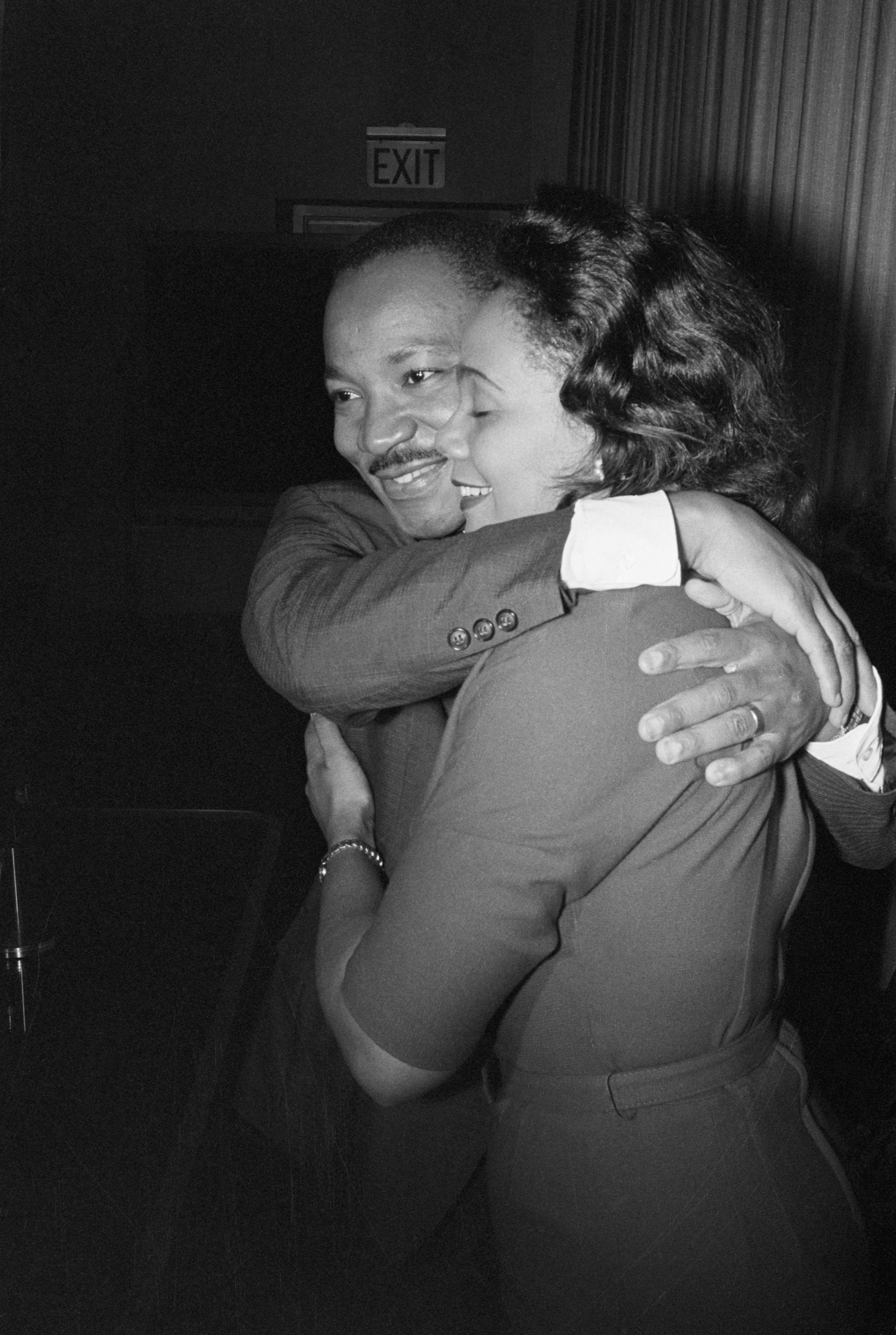

In Boston, Hank Willis Thomas’ permanent public sculpture “The Embrace” similarly encourages community and interaction, utilizing a very different approach. Willis’ historic monument to Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King employs abstraction to invite reflection, communion and engagement. The embrace refers to the hug the couple shared in 1964 after learning that King won the Nobel Peace Prize. It sits in Boston Common, America’s first public park, with a 400 year history of public gatherings.

Thomas’ challenge was to create an apolitical work in an era of relentless politicization. Thanks to the Internet, most people who “saw” this work, saw it only online, and therefore did not understand or appreciate its impact. Those who visited the work in person were deeply moved. Thomas’ sculpture is the largest monument to racial equity in the country. Being able to physically participate in the embrace at a scale of two stories tall and twenty feet wide by physically moving inside of it, gives people a chance to walk through the complicated, ever evolving history of MLK Jr’s impact on the story of humanity.

“We wanted to make a monument that... was a call to action, that reminder that we all have the potential to embrace another that could have a transformative, productive impact for society.”

Other public monuments like Maya Lin’s “The Wall” Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC and Peter Eisenman’s “Field of Stelae” Holocaust Memorial in Berlin utilize abstraction (and minimalism) to great effect to help people remember the most painful chapters of our pasts.

The role of the artist defies categorization, constantly adapting to fit into spaces left by unresolved cultural controversy and ideological debate. We look to artists to give us creative new tools with which we can navigate the most difficult issues of our times.

To that end, the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston is dedicating its annual Women’s Luncheon to a discussion on monuments, archives, memorials and memory. Newly appointed Barbara Lee Chief Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs Ruth Erickson will lead a discussion with Melissa Nobles, Chancellor and Professor of Political Science at MIT and lead collaborator of Northeastern University Law School’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice project. The ICA’s exhibition “Revival: Materials and Monumental Forms” shown in their East Boston Watershed space last summer addressed many of these issues.

Remembering is not a static effort, but one constantly tweaked by experience. Artists like Kara Walker, Kehinde Wiley, Simone Leigh, Maya Lin, Lauren Halsey and Hank Willis Thomas provide us with files on which we can sharpen our rough understanding, leaving us smoother edges with which to tease out historical truths from heroic legends and one sided myths we’ve been taught over time to believe.